Memory Management

With a built-in garbage collector, simple object literal syntax, and automatic "passing-by-reference"pass_by_reference for objects, it's easy to forget the impact of memory allocation on application performance. For every object created, space must be allocated on the heap. When the object is dereferenced, it must be cleaned up to make room for other objects. Depending on the browser, this may have varying performance impacts.

pass_by_reference. JavaScript isn't truly pass-by-reference. Rather, copies of references are passed to arguments. ↩

Garbage collection pauses can be difficult to identify. In most traditional web apps, a garbage collection pause may seem almost imperceptible. Longer pauses may make the interface feel unresponsive, as if the browser is stuttering before performing (or after performing) some sort of action. In other browsers, garbage collection pauses may have even more dire performance consequences: older versions of Internet Explorer perform garbage collection after every 256 allocationsie6_gc

ies_gc. http://pupius.co.uk/blog/2007/03/garbage-collection-in-ie6/ ↩

Garbage collection pauses (or GC pauses, for short) are most noticeable in games, where each frame has only a limited amount of time to be rendered. If the browser performs a garbage collection pass between two frames, the second frame will probably not manage to render on time, leading to a decreased frame rate.

I> Many games facing memory management problems will have a satisfactory frame rate but will tend to stutter or pause. These pauses may appear multiple times per second or periodically over the course of a few seconds. In some modern browsers, the pauses may be less pronounced and exist as subtle jerky "twitches" in the animation.

On the other hand, a game or application with a consistently low frame rate (i.e., when measured, each frame takes approximately the same amount of time to render) may not be experiencing garbage collection pauses.

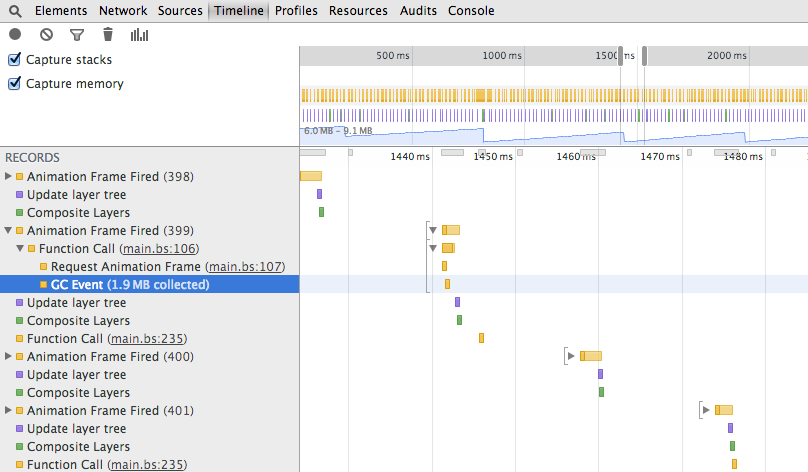

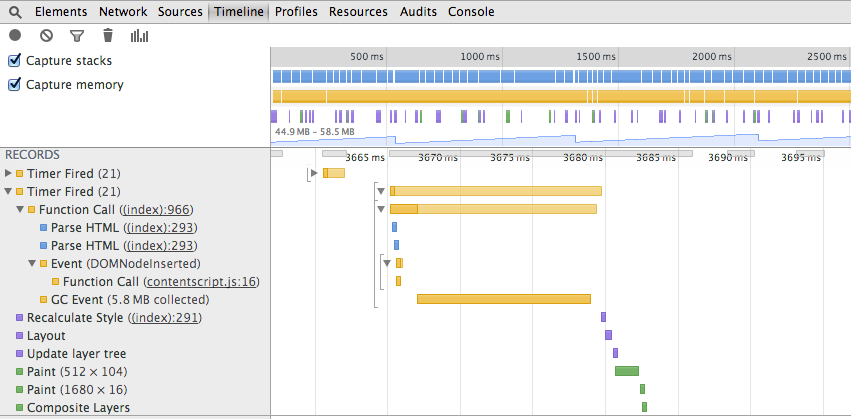

Confirming whether an application suffers from GC pauses is simple. The Chrome developer tools' Timeline tab gives a convenient insight into garbage collection pauses:

As you can see in the timeline above, requestAnimationFrame was fired, probably executing some sort of rendering function. Immediately afterward, a garbage collection was triggered, lasting approximately 0.2ms. This example is not so bad: the GC happens in an incredibly short amount of time; the rendering function executes very quickly. The result is that even with a modest GC pause, the frame rate is not affected.

The above timeline shows just how costly garbage collection can be. A pause of nearly 15ms causes at least one dropped frame every time it occurs.

Cause of garbage collection pauses

Garbage collection pauses wouldn't need to happen if there was no garbage to collect. Preventing garbage from existing in the first place is the only proper way to avoid garbage collection.

var players = ['bob', 'lucky', 'tiny'];

function getCoordinates(user) {

return [getX(user), getY(user)];

}

function drawPlayers(playersToDraw) {

for (var i = 0; i < playersToDraw.length; i++) {

drawAvatar(playersToDraw[0], playersToDraw[1]);

}

}

function draw() {

var coords = [];

for (var i = 0; i < players.length; i++) {

coords.push(getCoordinates(players[i]));

}

drawPlayers(coords);

requestAnimationFrame(draw);

}

requestAnimationFrame(draw);

Consider the above code snippet from a hypothetical game. This game would suffer from at least some minor garbage collection pauses. Can you spot the two issues?

- The array created by

getCoordinates(). One array is allocated for every player on every frame. At 60 frames per second with three players, that's 180 arrays that will probably be discarded almost immediately. - The array created by

draw()forcoords. Again, this is one allocation performed on each frame, leading to up to sixty allocations per second.

In this example, the garbage that's created on the heap is probably not severe enough to cause any major problems. In fact, if the game is simplistic enough, it may not be noticeable at all. Any game of substantial complexity (e.g., games that consume any notable percentage of their available rendering time), however, will quickly find that these allocations get far out of hand.

Addressing garbage collection pauses

Let's look at addressing some of these issues:

- Don't generate new coordinates on each call to

getCoordinates(). The list of players is stored in theplayersarray. Perhaps keep a persistent array or object calledplayerLocationscontaining the coordinates for each player. Recycle the same array of coordinates for each invocation. - Don't use an intermediate function. Instead of calling

getCoordinates()and passing the result throughdrawPlayers(), simply havedrawPlayers()callgetX()andgetY()directly. It may not be as clean, but it prevents the need to allocate any arrays at all. - Recycle temporary objects. By moving

var coords = [];outside ofdraw(), the same array can be recycled. At the beginning ofdraw(), all that is necessary is to remove each item from the array:while (coords.length) coords.pop();.

The following version of the above avoids the memory management issue by passing the coordinates directly to their destination. In doing this, an array (or multiple arrays) were not needed to store the values in question.

var players = ['bob', 'lucky', 'tiny'];

function draw() {

var player;

for (var i = 0; i < players.length; i++) {

player = players[i];

// Values are passed directly to their destination, avoiding any

// temporary object. At a larger scale, this may not be ideal

// because the code can get quite unruly.

drawAvatar(getX(player), getY(player));

}

requestAnimationFrame(draw);

}

requestAnimationFrame(draw);

In this next example, a series of pre-made arrays are used instead of allocating new arrays on each iteration of the game. Since setting the contents of an array or taking references to an array does not cause issues with garbage collection, this approach can also be used to safely avoid all of the aforementioned issues.

var players = ['bob', 'lucky', 'tiny'];

// A single object pool is used to store coordinates.

var playerCoords = [[0, 0], [0, 0], [0, 0]];

function updateCoordinates(index) {

// Existing arrays are updated with new values, recycling old objects

playerCoords[index] = getX(playeres[index]);

playerCoords[index] = getY(playeres[index]);

}

function drawPlayers(playersToDraw) {

for (var i = 0; i < playersToDraw.length; i++) {

drawAvatar(playersToDraw[0], playersToDraw[1]);

}

}

function draw() {

// No temporary array is created.

for (var i = 0; i < players.length; i++) {

updateCoordinates(i);

}

drawPlayers(playerCoords);

requestAnimationFrame(draw);

}

requestAnimationFrame(draw);

Some allocations are OK!

It should be noted that allocations are not always bad. In code that does not run frequently (such as code to handle button presses or general page interactions), allocations are common and completely harmless to application performance. Allocations become a problem only in code that runs very frequently or runs for a long time, like games or graphics-related code.

Even in code sensitive to allocations, it is not universally bad to perform allocations. Small numbers of infrequent allocations are perfectly fine. Where do you draw the line delineating which allocations are good and which are bad?

- Allocations are bad if they happen on every iteration of a loop. In a game loop that runs at 60FPS, one allocation operation per iterations would cause at least 60 allocations per second.

- Allocations are fine if they happen occasionally. If one allocation occurs once every 10 to 30 iterations of a game loop, that's infrequent enough that the JS engine will have no trouble keeping up.

- Allocations are bad if the number of allocations in the worst case grows non-linearly. If there are two objects in a game that cause four allocations every 100 iterations, but four objects cause 16 allocations and eight objects cause 32 allocations, the code will quickly approach a rate that exceeds allocating once per iteration.

- Allocations are fine if they are for non-ephemeral storage purposes. In the examples above, some arrays were used as two-tuples to temporarily store coordinates so they could be passed between functions. This is bad: these ephemeral objects could have been avoided by passing values directly. If the objects had instead been made more permanent used to store values for many iterations of the loop, that would have made them more satisfactory, since storing structured information is difficult without using the heap.

Browsers and garbage collection

Different browsers have different behaviors when memory-inefficient code runs. This is due to different types of garbage collector implementations across each browser.

At the head of the pack is Chrome with V8's generational garbage collector. In V8, memory allocation is cheap and there is a negligible performance impact from creating new objects. V8 includes what is known as a generational garbage collector. This means that objects that are allocated are segregated into different groups: new objects live in one place, and objects that have been around for a while move to another. Since objects that are new tend to become garbage quite quickly and old objects tend to stay around for a long time, separating the two greatly decreases the time to detect and clean up garbage. The detection phase is known as marking: the heap is scanned for pointers, and the objects they point at are marked as "still in use." The cleanup phase is known as sweeping: each of the objects that are not marked as alive are cleaned up. In V8, some of the sweeping phase can be performed on a different thread.

Perhaps surprisingly, IE11's garbage collector does not perform badly. IE11 uses a JavaScript engine known as "Chakra," which uses a proprietary garbage collector. Little is publicly known about its internals, however.

Firefox implements a mark-and-sweep garbage collector similar to that of Chrome, but it is (at the time of writing) not generational. This means that Firefox must scan the whole heap for garbage every time it performs a garbage collection, rather than only parts of it. This means that garbage collection in Firefox generally takes much longer. The properties of generational garbage collection also mean that Firefox tends to store objects in a much less efficient way compared to other browsers.